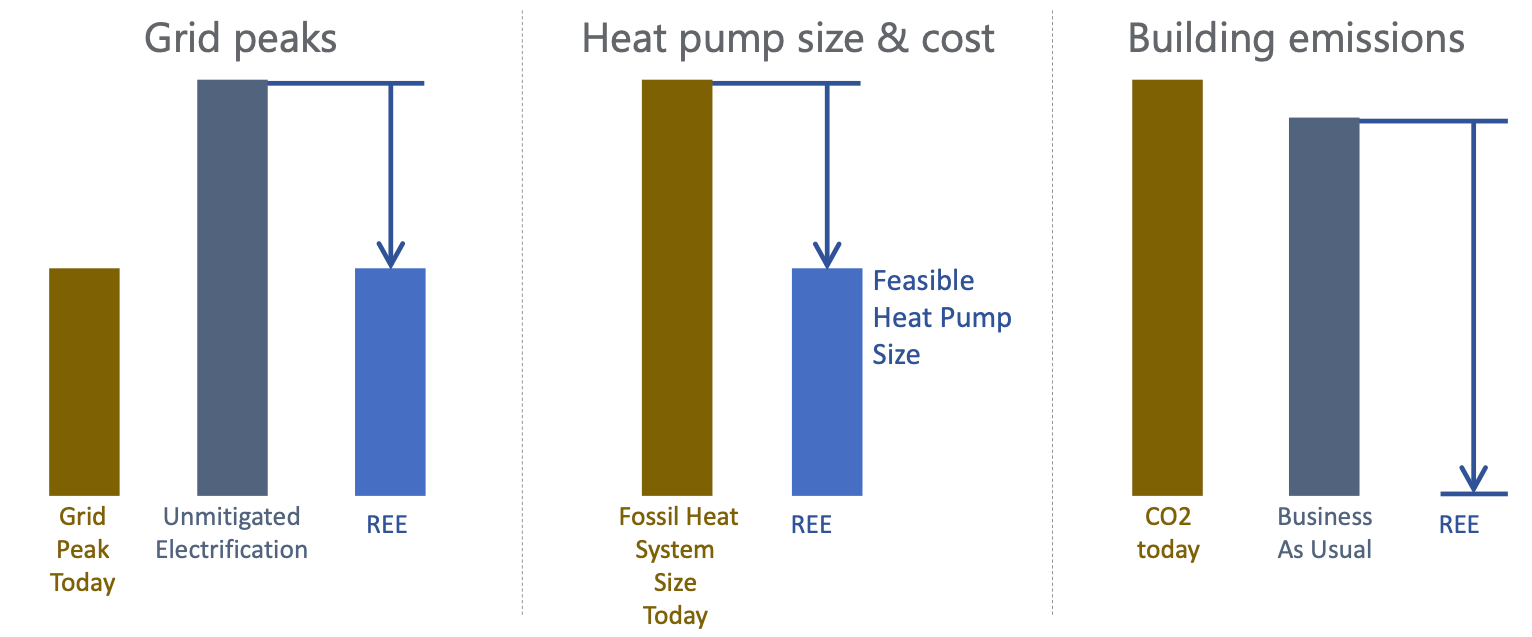

Perhaps because the electrification movement was born in mild-climate California, the cold-climate, tall-building narrative has for a time been incomplete. Decarbonization skeptics suggest that if it doesn't make sense to electrify everything in one simple move, then it doesn't make sense to electrify anything. Air source heat pumps have tremendously improved tremendously and may be a key component of electrification in cold climates, but they are likely only one part of the complete solution set for large and tall buildings. Such buildings must overcome space constraints and distribution challenges to provide comfort at peak load conditions without straining the electric grid or requiring oversized, sticker-shock-inducing equipment capacity.

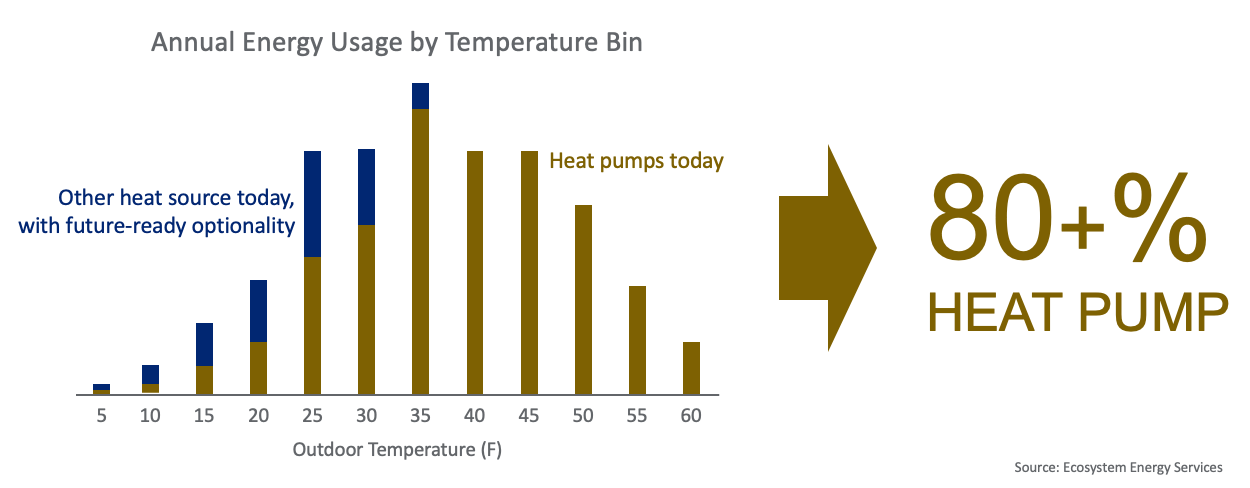

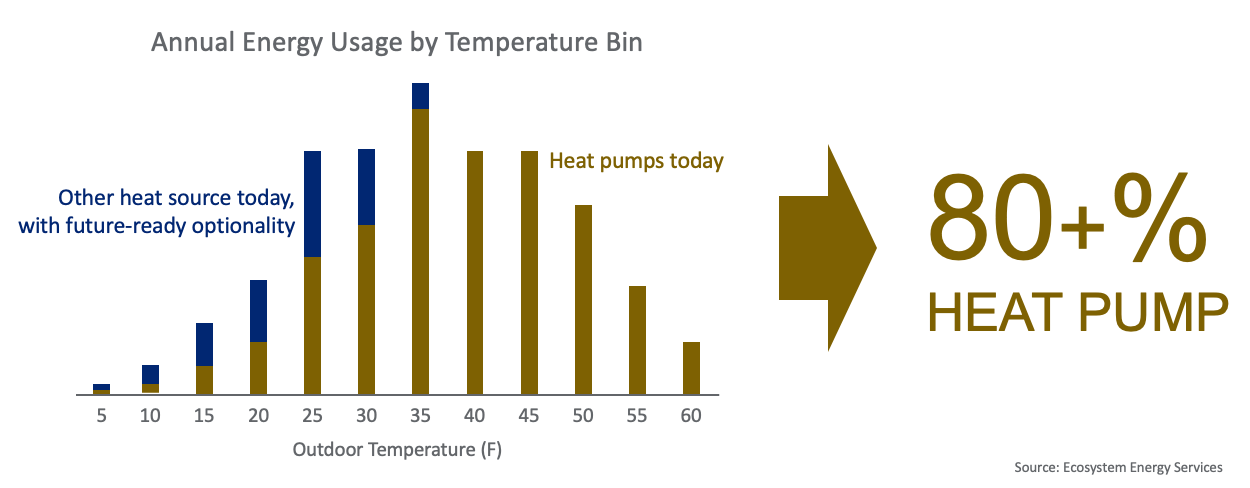

A more suitable chant for Northeast electrification cheerleaders should be Electrify Everything . . . Efficiently. Engineers should model building energy consumption data across granular temperature bins (see Figure below) and plan for electrification with “easy” loads like domestic hot water, then mild temperature loads (typically representing 80%+ of total loads), and finally for the extremes. This is the cascade approach. Until a viable solution emerges, a building owner might even keep a small gas-fired boiler and their steam radiators around as a reserve as they learn to grapple with resilient functionality at heating design conditions. Despite global average temperatures increasing, cold snaps may even become more extreme thanks to a collapsing winter Polar Vortex.

|